Five Songs That Just Hit Different That One Time

On Left of the Dial, our hosts often speak of the ways our environment has the potential to affect how we experience music. Last week, Kitzy mentioned the fact that they were not particularly taken by the final tracks of the new Acceptance EP, Wild, during their first listen through, but when it came to relisten as they recorded the episode, something clicked and by the end, Kitzy had confidently (and only half-jokingly) claimed that the last song, “Wasted Nights,” was not only their favorite, but objectively and categorically, the best song on the EP.

I almost always know how I feel about a song before I’ve finished my first listen through. However, every so often a song that I didn’t connect with in any notable way the first, second, or even fiftieth time through will come back around and become an entirely new thing for me, and it almost always has something to do with a particular set of environmental circumstances encouraging me to experience the song differently. So, here are five songs* that, due to some novelty of circumstance, I have come to understand in a wholly new and significant way.

*See the end of this post for a playlist of all seven songs mentioned here.

5. “Ostrichsized” - Lifetime

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a dirty little Jersey rat must love Lifetime. Because there are only 4 full length Lifetime records (and only two of them really count), all of their songs are precious to me, but my favorites have always been “The Gym is Neutral Territory” and “Rodeo Clown.” Some of the songs on this list, it is quite easy to see why the circumstances of a particular listen shifted how I experience the song, but this one is much less overt. It is simply this: “Ostrichsized” it turns out, is best listened to in a Target parking lot on a late June evening as the sun sets in colors so unbelievably saturated that you have to take a picture to commemorate the occasion, and when you post it to Instagram, the “nofilter” hashtag is warranted and sincere.

4. “Mass Pike” - The Get Up Kids

I guess “Mass Pike” isn’t a total match for this list, as it has always been one of my favorite Get Up Kids songs. What I will say, though, is that finally listening to this song while driving on the actual Massachusetts Turnpike, in the middle of the night, in the middle of winter (It’s a holiday song for me. Those are sleigh bells in the beginning, and you can’t tell me otherwise), with a person I had fallen in love with—he was not yet aware of this fact—riding shotgun and humoring me by letting me blare this song, even though he definitely thought he was too cool for my music, and for that matter, anything I liked, (half the reason I fell in love with him, of course) lit something up in the part of my brain that will forever be sixteen and searching for somewhere to belong.

3. “Kill the Messenger” - Jack’s Mannequin

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken so much from us, and one of the things that has made the last six months borderline unbearable for me is the lack of live music. I don’t remember the last summer I spent not bouncing around the Eastern half of the contiguous United States of America attending shows. So when Andrew McMahon announced that he would be visiting New Jersey to play two nights in celebration of the 15th anniversary of Everything in Transit, an album released by McMahon’s second band, Jack’s Mannequin, I was apprehensive, sure. Live music is so much about community. Without the shoulder-to-shoulder proximity of the crowd, would I even feel like I was really there? But even with those worries, I was not about to miss this opportunity.

Attending a drive-in show was odd, and I was right to think it might feel a bit isolated. But it was not without its benefits and charms. For one thing, if it got too hot, I simply turned on the air conditioning. The music, though we could hear it just fine through our open windows, was also being broadcast on a station on the radio, so we were able to pipe it directly into our cars, which gave me a level of control over the volume that I quite appreciated. One delightful aspect was the addition of horns to the applause at the end of each song. This might be the Jersey talking, but there is something intensely satisfying about a song finishing and then being allowed—nay, encouraged, to really just lay into your horn.

So the experience was, overall, more pleasant than anticipated. However, something happened that night that bordered on the magical. The weather all day had been lovely. A little humid, but not unbearable. Clear skies, light breeze, etc. Halfway through the fifteen song set, McMahon and company began playing, “Kill the Messenger,” a song that appears on that first Jack’s Mannequin record. I need to reiterate that until this point, the skies had been clear. It was just beginning to move from dusk to darkness, and as the sun set, golden, behind us, McMahon sang through the first chorus. He reached the line, “I’m gonna send a little rain your way,” and the skies just . . . opened up. Suddenly, fat little raindrops were bouncing off all of our windshields. People turned their wipers on, and as is the case with most newer cars, their headlights also joined the party. An ocean of cars, a sea of people, alone but together, bathing the parking lot in light. Andrew sang, “I’m gonna send a little rain to pour down on you,” and the rain fell. I have never been part of something that felt so full of magic. I swear, you could almost see it, incandescent, sparking like static electricity, in the air. As the song finished, the rain shifted to a downpour, and then the lightning started. The stage was cleared to thunderous applause (you’ll allow me this indulgence of the cliche, I hope. What with the lighting and all), and then we all waited, safely in our cocoons, for the storm to pass, which, of course, it did. They always do.

2. “Up the Wolves” - the Mountain Goats

Every semester I teach close reading. I maintain it’s one of the most crucial skills a person can cultivate. We’d be in a much better place if we were a nation of skilled close readers. Sometimes I use essays or short stories. Sometimes I use poetry. Occasionally, a video game (Gone Home works so well for this exercise). A year ago, I was teaching a new class at a new university, an hour drive from my home (this is not relevant to the story, but I must complain about being an adjunct professor anytime the opportunity presents itself, despite how much I love teaching), and I was using song lyrics to introduce close reading to my students. On previous occasions I’d used Beyoncé’s “Formation” and Childish Gambino’s “This Is America.” This time, I decided to pick a song that I felt was rich with imagery but lighter on explicit message. I didn’t want my students reaching for outside context to do this work. I had assumed, wrongly, that some of them may have recognized “Up the Wolves” from its use on The Walking Dead. None of my students knew this song. And what I’d neglected to consider was the fact that because of this, my students encountered this song as if I had pulled it from the ether as some kind of reflection of my own identity and personhood. As we listened to and read through the lyrics, I watched many of their expressions change from blank-faced boredom, to confusion, and in a couple of cases, finally, to mild concern. “I'm gonna bribe the officials. I'm gonna kill all the judges,” Darnielle sings, the melancholy, fragile-hearted Kermit the Frog that he is. “It's gonna take you people years to recover from all of the damage,” he just about yelps. And my students, in one of the very first classes of their first year of college, I could see them looking around to one another, thinking “Is this normal? Is this what college is going to be like? Should we tell someone about her?” I’ve been teaching for a few years, and I’ve always been proud of my ability to come across as if I’m an actual human being (I’m not, but I like coming across as if I might be). But it was in this moment that I realized it is not always my job to come across as an actual human being because sometimes you show your students who you are and they are, understandably, deeply disturbed.

I do think it’s worth mentioning that I’d almost used the song “Autoclave.” Knowing their reaction to the relatively benign “Up the Wolves,” I can imagine their faces now if I were to stand at the front of the classroom and say, “Of course Darnielle doesn’t believe his heart is literally an autoclave, yes? What do we call this? A metaphor! And in what ways can a heart be an autoclave? Anyone? No? Is it that his heart is so sterile and incapable of feeling, compassion, empathy—all the things that make being human worthwhile—that he’s sure no one will ever love him? Could be! Now here’s a tough one. What literary device is Darnielle employing in the last line of the verse that begins ‘I dreamt that I was perched atop a throne of human skulls,’ and ends ‘Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name’ Anyone? No, not the dream about the throne of human skulls! That’s an obvious one. The last line. It’s from Cheers? You all know Cheers? The famous television sitcom from the 80s? Come on, folks! It’s an allusion! He’s highlighting the human desire to be known by another despite our deep understanding that this can never truly be achieved! Anyway, don’t forget your first drafts are due Monday! Have a great weekend! Class dismissed!”

1. “Hold Me Down” - Motion City Soundtrack

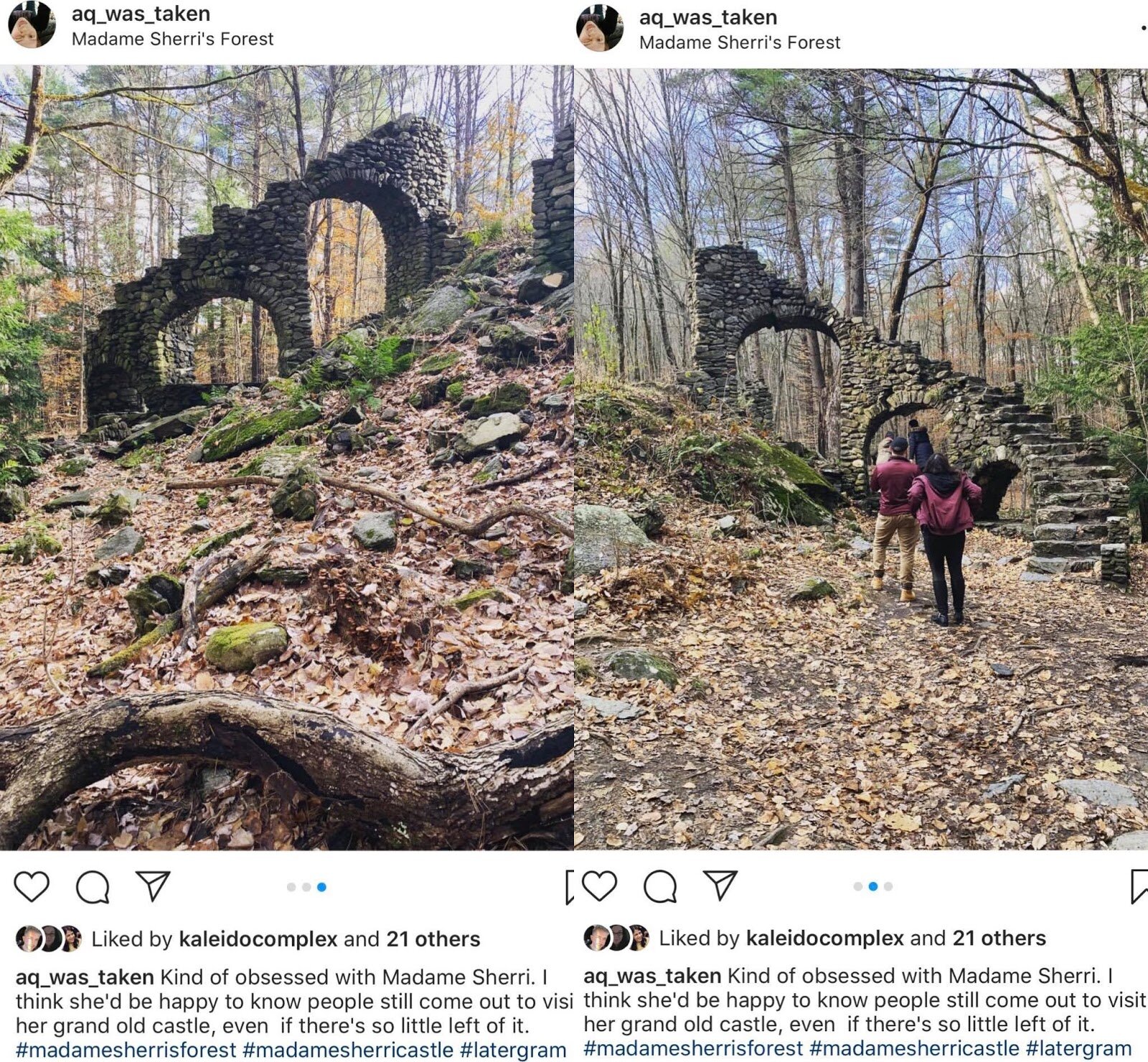

Madame Sherri’s castle ruins, resting in the unbelievably sleepy town, West Chesterfield, New Hampshire, sit a short way back from the trailhead, and if you visit outside tourist season, before the leaf peepers come through on their way to the much more metropolitan town of Brattleboro in neighboring Vermont (At least two coffee shops. A proper brewery. Antique shops. The whole nine), you can catch Madame Sherri and her castle ruins unoccupied. Deserted, in the gray light of late fall, they feel like hallowed ground.

Madame Antoinette Sherri is the kind of legend I cannot believe more people don’t know about. You can (and I highly recommend you do) read Jeff Newcomer’s lovely, compassionate history of her here. Learning about her had the same effect on me that learning about the Kennedy cousins had the first time I watched Grey Gardens. Like Little Edie and her mother, Madame Sherri was a larger than life character who seemed to have trouble finding a place to really belong. Newcomer writes, “Antoinette became famous (or infamous) for the parties she threw for visitors from the city. She was said to have greeted her guests from the top of the castle’s spiral staircase or sitting regally upon her ornate throne, dressed magnificently in costumes from her Broadway shows.” I can’t help but think she must have been a lonely person, lonely with the kind of desperation that inspired her to build a grand mansion in the hollow of a valley, at the bottom of a mountain, in the middle of the woods, in the middle of nowhere and then invite guests to visit her mansion and revel in its grandness. And visit they did. At least, for a while. But, as Newcomer tells us, Sherri was not a wealthy woman, and in 1962 the ostentatious house in the woods, which by then had fallen into disrepair, was destroyed in a fire, leaving only the foundation and the staircase. Three years later, at 84 years old, Madame Sherri died, destitute and considered a ward of Brattleboro. Today, you can visit the foundation and this staircase leading nowhere, still standing by what seems to be the sheer force of will.

My last trip out of West Chesterfield began at 5AM on a Monday. I had to teach my English 101 course in Camden, New Jersey later that afternoon. I could have left a little later, but I wanted to stop by and say goodbye to my girl and her pile of stubborn bricks that refuse to fall. I covered the short walk from my car to the grounds, my fingers crossed that I’d be alone, and aside from a few fat birds pulling fat worms and who knows what else from under the rotting wet leaves that gathered in the foundation’s corners, I seemed to be by myself. Because I am a sensible person (haters don’t @ me), I did not ascend the brick staircase to nowhere, as it was covered, slick and oily, in that same dank vegetation on which the birds were currently gorging themselves. Instead, I sat cross-legged in the middle of what I always imagine to be the ballroom (truth be told, I can’t say with any certainty the house even had a ballroom, though it seems inconceivable that it would not have). Now, it looks like a low, wide stage, crumbling pillars rising at the corners, the foundation exposed from years of pedestrian traffic and natural erosion. I’d planned to spend that early hour with Madame Sherri, reading a bit to finish preparing for the class I was teaching that afternoon. (I just now checked the syllabus from that semester. We were discussing Paul Bloom’s “The Case Against Empathy” that week). I opened and shuffled a playlist that I listen to when I need music I know well enough that it will not distract me from whatever task I am trying, usually in vain, to complete. “Hold Me Down” isn’t a particularly obtuse song. It is not difficult to parse its meaning. “Hold Me Down” is a breakup song. The singer reads over a letter left by their partner who cannot stay because the singer has become a kind of heavy, weighted presence in the letter-writer’s life. It is a straightforward, almost common scenario, heartbreaking though it is. None of this was new to me on that listen. I had heard it dozens of times, easily, before. So I can’t say for sure what affected my listening so profoundly this time. It’s as if there were something at play in the air that brought the song, and the castle, and the moment, together in such a way that . . . Okay, it was not as if I were suddenly hearing “Hold Me Down” for the first time. It was more like up until now, I had missed something critical in the song, something that was thrown into stark relief when shorn against the ruins of Madame Sherri’s castle. I don’t know that I’ve been able to capture the feeling since—though lord knows I’ve tried.

Here it is, best I can explain it. There is a moment toward the end of the song. Justin Pierre sings the chorus: “You're the echoes of my everything / You're the emptiness the whole world sings at night / You're the laziness of afternoon / You're the reason why I burst and why I bloom.” Every other time these lines are sung, they precede the question “How will I break the news to you?” but this time he adds, “You're the leaky sink of sentiment / You're the failed attempts I never could forget / You're the metaphors I can't create / To comprehend this curse that I call love.” I have heard these lyrics many times, but usually in the comfort of my car or my home. Places that are familiar and mundane. Madame Sherri’s castle, no matter how many times I’ve visited, feels neither familiar nor mundane. Madame Sherri’s castle is beautiful but haunted. And “Hold Me Down” is that kind of song. It’s a beautiful song. But it’s a haunted song. In fact, after Pierre laments the ineffability of love’s curse, he falls back into his plaintive question, “How will I break the news to you?” This time, though, he repeats himself a handful of times, fading away, echoing in the final moments as the song ends. In this particular instance, I imagined it escaping the confines of the song itself, traveling through the damp morning air, landing somewhere out in the trees. This question asking itself over and over, never answered.

Photo restoration by Newcomer partridgebrookreflections.com

And if you imagine Madame Sherri’s castle as it was in the 1930s, if you imagine Madame Sherri perched at the top of her staircase, dressed in all her feathers and false eyelashes, and if you pretend for a moment that this song is being played, albeit anachronistically, by the band who, moments prior, had been tuning their instruments on the ballroom floor below, if you imagine them playing this song to a house full of people Madame Sherri knew did not love her but whose love she so desperately wanted that she was willing to build a grand mansion in the hollow of a valley, at the bottom of a mountain, in the middle of the woods, in the middle of nowhere—an altar to the project of cultivating, of somehow deserving, that love—I think, maybe, if you imagine that, you can hear this song the same way I did.

Andrea Quinn cohosts Set Condition One