Josh Ruben’s Shudder Original SCARE ME Is a "Campfire Movie That Never Leaves the Campfire”

[NOTE: You can watch the trailer for Scare Me by scrolling to the very bottom of this post, but honestly, just go watch the movie.]

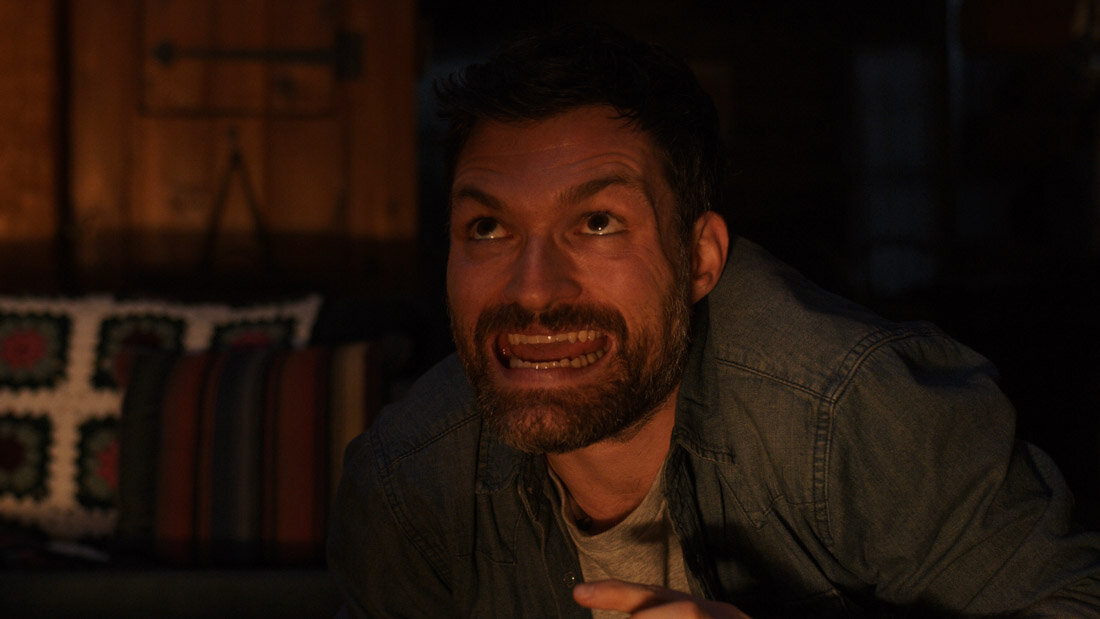

There is a rare kind of joy that comes with the realization you’re watching one of your favorite movies for the first time, and Josh Ruben’s first full-length feature Scare Me will undoubtedly become a new favorite for many horror and comedy fans alike. In today’s bonus episode of Never Heard of It, Ruben, who plays struggling writer Fred Banks, describes his movie as a “dark comic thriller with horror elements,” as a “talkie with psychosexual undertones,” and as a “campfire movie—an anthology movie—that never leaves the campfire.” Scare Me, which stars Aya Cash, Chris Redd, and Ruben (who also wrote, directed, and produced the film) made its debut at Sundance in January of 2020 and was released today (October 1st) exclusively on the horror-focused streaming service, Shudder.

Described over and over in post-Sundance reviews as “metafictional,” Scare Me has a crystal clear understanding of the space it occupies and the kinds of viewers that make up its audience. It takes the tropes those of us who grew up on a steady diet of horror movies are intimately familiar with, shakes them up, spills them out on the floor of a dimly lit cabin (for the most part, the film’s only location), and rolls around gleefully in those conventions: in the flash, for example, of the knives Fred’s fingers dance across as he passes by them on his way through the cabin in the daylight hours, in Fred’s silhouette, framed in the doorway at the top of a narrow staircase leading into a dark, unexplored basement. In these and many other instances, Scare Me feels positively steeped in its love for movies in general, and horror in particular. In fact, you might make a drinking game of the many references Fred and Fanny make to other movies as they tell their own tales. On a set as spare as this one, these references help define the various scenes the two create for each other, and Ruben for all of us.

There is a lot to love about this movie, but what makes Scare Me so special is the way it celebrates the power of collaborative storytelling. Fred and Fanny are driven together under fairly typical horror movie circumstances: two writers (well, Fanny actually writes; Fred spends a lot of time thinking about the fact that he should be writing) happen to rent neighboring cabins where they each intend to do some writing. When a power outage leads Fanny to Fred’s cabin, she suggests they while away the time telling each other scary stories. Fanny’s a natural. Fred, not so much. And the tension, at times so thick you might cut it with one of those knives Fred helpfully points out to us earlier, builds from there.

Yet, even in Scare Me’s darkest moments, it is difficult to ignore the freedom and exuberance in the performances of our lead actors. Although, as Ruben explains in today’s Never Heard of It, “every word of [Scare Me] was scripted,” his improv background is still clearly an asset. There is not one moment in Scare Me where he appears to be holding back, nothing to imply self-consciousness in his performance. Cash’s performance, too, is gleefully uninhibited. The actors pull ugly faces, make weird noises, contort themselves grotesquely for their own, and for the audience’s, entertainment. As Fred and Fanny work together to tell their tales, the scenes come alive—not only figuratively but also it seems, to varying degrees, literally—around them. Many of these moments do feel supernatural, as the environment bends and shapes itself around Fred and Fanny’s words. Though these scenes stand primarily as testaments to the power of imagination and storytelling, it is sometimes difficult to say whether or not something else is going on here. Are we waiting to find out there’s something lumbering—err, lurking—in the woods? In the basement? In the attic? Could the cabin be haunted? Are Fred and Fanny unintentionally summoning some dark presence with their scary stories? (That’s actually a pretty cool idea. TMTMTM.) Is dear Bettina, Fred’s chatty, aggressively upbeat driver from the film’s start, played so joyously by Rebecca Drysdale, waiting for the right time to burst out from behind a curtain and slash our two leads to pieces? And what the hell is up with Carlo, Chris Redd’s impossibly charming pizza delivery guy?

Early on in the film, Fanny pushes Fred to tell the werewolf story he claims to be writing, and when he finally acquiesces, Fanny makes a big show of it, clapping and calling out loudly to an imagined audience. “Lower your voice,” Fred tells her, and Fanny glances upwards. “What?” she asks, her eyes trained on the ceiling, “You afraid you’re gonna wake the woman in the attic?” Everything you need to know about Scare Me is located in this line if you sit for a minute with the many implications it contains. First, of course, Fanny is referring to the horror trope of the spooky old lady hidden away from the rest of the world, possibly as a ghost haunting the house in which she was wronged, but in any case, as a frightening female presence. We know this is an intentional reference; as the absolutely exquisite sound design draws our attention to the floor above Fred and Fanny, we hear Fanny’s eerie vocalizations intermingle with the sound effects and music that build on her voice and add weight to the woman the two writers seem to be imagining into existence. She creeks. She thumps the floorboards. Her presence is all but literal.

Whether intended or not, there is also an explicit literary allusion at work here, to Bertha Mason, first wife of brooding Rochester in Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre. One of the major conflicts in the novel is Bertha’s being hidden away, as the possibility of her appearing threatens Rochester and his budding romance with the young Jane Eyre. We learn little about Bertha, but her main crime seems to be that she was too unruly, unwilling to behave as Rochester would prefer. In the nearly two centuries since, Bertha’s come to represent the ways in which women’s lives are negatively affected by patriarchal oppression. Bertha is the original woman in the attic, and whether or not Fanny expected Fred to recognize this, Fanny’s words come loaded with that history. We can follow the thread further though, to feminist literary critics Gilbert and Gubar’s 1979 work, The Madwoman in the Attic : The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, the book’s title making a direct allusion to Bertha and other 19th century characters like her: women written by men, their refusal to remain pure, docile, gentle leads to their authors characterizing them as monstrous. In contrast to characters like Bertha, Gilbert and Gubar offer the image of the angel, who is all of those things Bertha isn’t. In response to the limiting nature of these two representations, Gilbert and Gubar call for a dismantling of both halves of the dichotomy in favor of women writers writing themselves into existence on the page (and screen, of course). We can read Fanny’s attempt to do just that in the success of her own horror novel, Venus.

Fanny herself defies easy categorization, though she has much more in common with Bertha than any angel of the house. She is loud, unapologetic, driven, and it seems that everything Fred wants to do, from writing a best-selling novel, to building a fire, to ordering a pizza, Fanny can already do better. The tension that crackles underneath every exchange between Fred and Fanny is fueled by this fact. Fanny knows she’s better than Fred, and she isn’t afraid to tell him so. Fred must know on some level, but his refusal to admit it leaves him bristling with anxious energy. So when Fred tells Fanny to “lower her voice,” Fanny’s response speaks to several possibilities. There is the possibility of waking the madwoman who haunts, figuratively and literally, so many male-authored novels from the 19th century on, and just maybe, the cabin our two authors currently occupy, as well. And as Fred makes it clear that he’s threatened by strong, successful women, to wake the madwoman in the attic might also be to incur the wrath of the full history of women who have refused to be silenced by overbearing men. And then there’s Fanny. “Lower your voice,” Fred insists. And what he means is “make yourself smaller, less. Let me control this room.” Fanny’s response, then, is a challenge, the “Keep pushing, Fred. You don’t want to wake the monster in me,” is unstated but heavily implied. None of this is to say that Ruben was intentionally alluding to Jane Eyre and/or Gilbert and Gubar’s foundational feminist text, only that it is worth considering, especially in a film so concerned with the power that words hold, the full weight of Fanny’s question.

It is breaking no ground to say that horror is the lens through which we examine our own real world anxieties. As Jeffrey Jerome Cohen tells us in Monster Theory: Reading Culture, monsters act as “as an embodiment of a certain cultural moment—of a time, a feeling, and a place . . . The monstrous body is pure culture. A construct and a projection, the monster exists only to be read.” That is, we use the metaphors horror affords us to work through the very real fears that populate our waking hours. The monsters appear; they stand in for something else—something real—that lurks beneath the surface. Defeating the monsters fuels us to fight the real dangers in our lives. An oft-cited example of this pattern is the proliferation of zombie films in the wake of the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, but Ruben is clear about the specific horrors that led him to writing this movie. As he explains on Never Heard of It, “For me, the angry drive, or the motivation writing this, was where the world was at. People who I looked up to, like Aziz Ansari, were being outed for taking advantage of women, and a lot of guys in my network, a lot of dudes, were pretty quiet on Instagram and Twitter, and all I was doing was hitting the ‘Share’ button.” In fact, the werewolf story Fred tells early in the film would make an easy allegory for the Me Too movement: a story about a man who might seem safe on the surface, but who can’t help revealing his monstrous nature, and the woman (women) he threatens. It is not a long walk from Fred’s werewolf tale to the many men in Hollywood whose predatory natures continue to be revealed (if I were a better person, I could move past this sentence without drawing attention to the incredible restraint I’ve exercised by not making a tale/tail pun, but here we are). It will be no surprise if we see an uptick in werewolf-ish movies in the coming years. In Scare Me however, we do not have to read between the lines, unpack the symbolism, identify the “hidden message.” Rather than the elements of horror acting as an overlay to mask what really scares us, the real world issues at play are out in the open, and it is the supernatural that lurks in the corners of this film.

Scare Me is available now, only on Shudder. You can sign up for a free 7 day trial, but trust us, once you see all the good stuff Shudder has to offer, you’ll want to sign up for life. (We came for the Scare Me, but we’re staying for the WolfCop.)

Listen to Ruben and the Never Heard of It gang talk Scare Me below! (You can also watch here. )

Andrea Quinn is Night Shift Radio’s social media manager and one third of the crew of Set Condition One. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.